John Jay: New York’s Federalist Figure

By Jack Campbell

Programs & Events Associate Jack Campbell explores the legacy of statesman, diplomat, Supreme Court Justice, and native New Yorker John Jay.

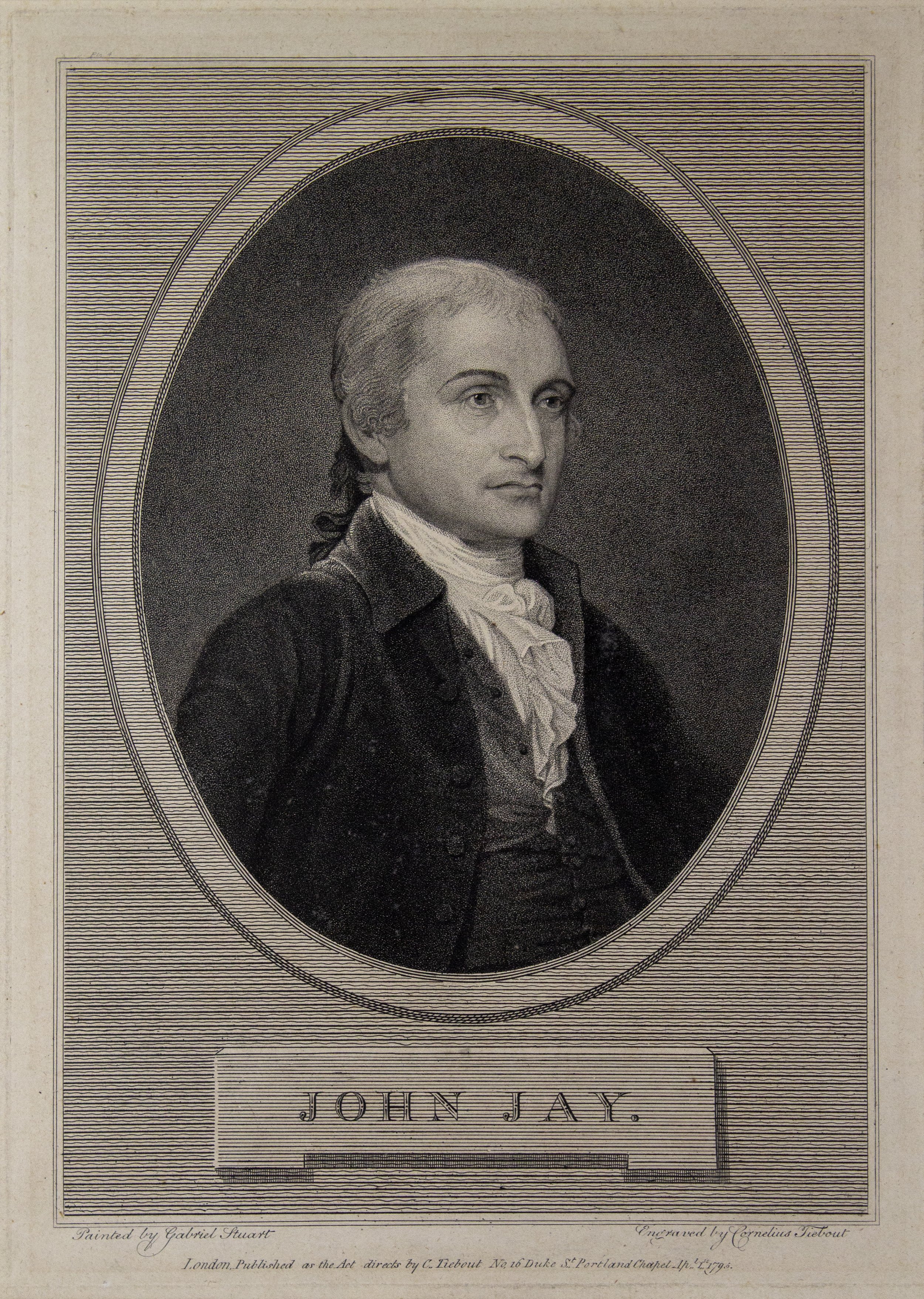

Cornelius Tiebout, John Jay, FRAUNCES TAVERN MUSEUM COLLECTION

Native New Yorker John Jay was a statesman, diplomat, and first Supreme Court Justice who helped define the Revolutionary era as a significant Federalist figure. Among his most notable roles was the Secretary of Foreign Affairs under the Articles of Confederation, to which he was appointed in 1784. This department would eventually become known as the Department of State.

Much of Jay’s work as Secretary of Foreign Affairs occurred at 54 Pearl Street. He carried out many of the duties that are now associated with the Secretary of State. He served as the young country’s chief diplomat, for which he was well qualified due to his time as an ambassador during the Revolutionary War. As the country struggled under the Articles of Confederation, Jay’s job would have been challenging. [i]

Jay was born in 1745 in New York City to Peter and Mary Jay. The Jays were one of the oldest and most prominent families in New York City, descended from French Huguenots who had immigrated to the colonies decades before. His mother was a member of the Van Cortlandt family, another of New York's oldest and most prominent families and a legacy of New York's Dutch origins. He would spend much of his childhood in Rye, New York, north of the city. These familiar connections would aid Jay immensely as he made his way in the world.

Elected to both the first and second Continental Congress as a delegate from New York in 1774 and 1775, Jay evolved into an ardent supporter of independence. Initially, he had been a moderate and even resigned from Congress rather than sign the Declaration of Independence. This was because he felt that reconciliation with Britain was still possible. [ii] As debates raged and it became clear that the British would not give in, Jay became more and more convinced that total separation between the two was necessary. He quickly became one of the Declaration’s greatest supporters as his views strengthened. This was especially important because he came from New York, one of the more reluctant colonies to support independence, as it had a significant Loyalist population.

In 1779, he was appointed to be the American ambassador to Spain. There, he would begin his diplomatic experience that would set him up for his future role as Secretary of Foreign Affairs. He worked on negotiating a potential alliance with the Spanish and laying the foundation for a future relationship between the two countries after the war. When peace negotiations commenced with the British in 1781, Jay was among those chosen as the American representatives. He would help draft, and would then sign, the Treaty of Paris in 1783. [iii]

Upon returning to the new country from Europe in 1784, Jay learned that Congress appointed him as the new Secretary of Foreign Affairs. Upon hearing the appointment, the Marquis de Lafayette remarked that “I hope you will accept; I know you must.” [iv] This role, much akin to the present Secretary of State or a Prime Minister, was among the most important in the new government under the Articles of Confederation. Unfortunately, the weakness of the Articles made his job incredibly difficult. Jay quickly became convinced that a strong central government was necessary and became among the most prominent Federalists in the country.

Jay strove to make the best out of the difficult situation. He worked at enhancing the United States’ world standing and establishing its foreign affairs connections. He corresponded regularly with the likes of Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, the American ambassadors to France and Great Britain, respectively. [v] He knew to only trust European powers to a certain extent. [vi] He believed that high morals were necessary for the country’s success and strove to apply them to his work as America’s chief diplomat. This meant espousing that America should strive to be in the moral right on issues and continually work to do good acts. [vii]

During this period, Jay began his participation in The Federalist Papers alongside Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. These notable works argued for a strong central government and the ratification of a new Constitution. [viii] Hamstrung by a weak and ineffective confederation government convinced Jay they needed to do more. While he negotiated with Congress for more autonomy, he understood the need for more federal power. [ix] He pushed for New York to ratify the new Constitution in 1787 and publicly advocated on behalf of it. If America was to survive, Jay knew that something had to change.

Jay worked extensively at 54 Pearl Street during his tenure as secretary. He worked at conducting business, writing correspondence, and attending meetings here. He was kept very busy as one of the government's most influential figures. It would remain his primary office space throughout his tenure as secretary.

UNKNNOWN ARTIST, JOHN JAY, Fraunces TAVERN MUSEUM

After the Constitution's ratification and President George Washington's election, Jay was appointed as the first Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1789.[x] His time as chief justice was notable for a treaty Jay negotiated in another diplomatic role in 1794. Commonly referred to as the “Jay Treaty,” the “Treaty of Amity Commerce and Navigation, between His Britannic Majesty; and The United States of America” intended to resolve outstanding disputes with Great Britain.[xi] It was highly controversial due to concessions made by the Americans and it hurt Jay’s reputation. Opponents argued that it was a capitulation to British interests, while sympathizers believed it was the best deal America could have received.

Jay would serve until his election as Governor of New York in 1795. One of the most notable accomplishments of his governorship was signing An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery in 1799. While not immediately ending the institution of slavery in New York State, the act freed enslaved children born after July 4, 1799, but they were classified as indentured servants until a certain age. They could not be legally free until the age of 28 for men and 25 for women. [xii]

Jay would serve as Governor until 1801, when he retired from public life. He had been married to his wife Sarah since 1774, and they remained married until her death shortly after his retirement. On May 17, 1829, Jay died at his home in Bedford, New York, after being stricken with palsy. Nevertheless, he left behind a storied legacy of diplomacy, statesmanship, and governance, cementing his place as one of the most important figures of the early nation.

Endnotes

[i]Kaminski, 295.

[ii] “Founding Fathers.”

[iii]“John Jay: Secretary of Foreign Affairs.”

[i]Kaminski, 300.

[v]“To John Adams from John Jay;” “To Thomas Jefferson from John Jay.”

[vi]Kaminski, 304.

[vii]Kaminski, 295.

[viii]Meehan, Federalist Papers.”

[ix]Kaminski, 295.

[x]“John Jay: Secretary of Foreign Affairs.”

[xi]Grimm, “Jay.”

[xii]Sudderth, “Jay and Slavery.”

Footnotes

Department of State. “John Jay: Secretary of Foreign Affairs.” National Museum of American Diplomacy. https://diplomacy.state.gov/people/john-jay/.

Grimm, Kevin. “John Jay.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/john-jay/.

Harvard University. “Did any of our ‘Founding Fathers’ NOT Sign the Declaration of Independence?” Declaration Resource Project. https://declaration.fas.harvard.edu/faq/founding-fathers-not-signers

Kaminski, John P. “Honor and Interest: John Jay's Diplomacy During the Confederation.” New York History 83, no. 3 (Summer 2002), 293-327.

Meehan, Adam. “Federalist Papers.” George Washington’s Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/federalist-papers/.

National Archives. “To John Adams from John Jay, 19 August 1786.” Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Adams/06-18-02-0233.

National Archives. “To Thomas Jefferson from John Jay, 3 November 1787.” Founders Online. https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-12-02-0303.

Sudderth, Jake. “Jay and Slavery.” Columbia University. https://web.archive.org/web/20070208183047/http://www.columbia.edu/cu/lweb/digital/jay/JaySlavery.html.