Who Illustrates History?

By Lisa Goulet, Collections Manager

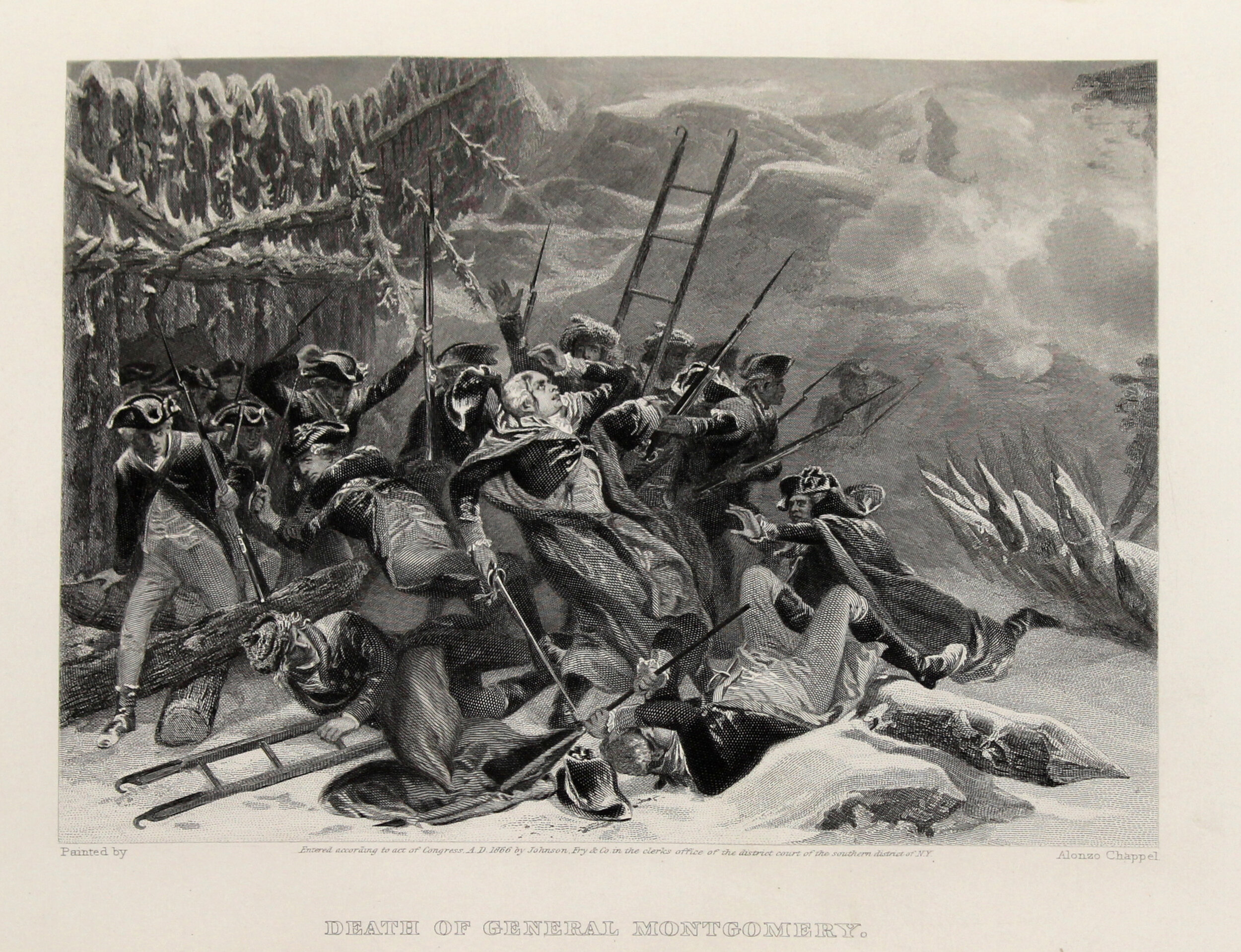

In January 2019, the Museum received a generous gift made by Kent D. and Tina K Worley. This collection spans the breadth of material culture from and about the Revolutionary Era, including military and tavern-related artifacts, art, documents, and maps, including this mysterious engraving.

Unknown engraver, after Alonzo Chappel (American, 1828-1887)

Death of General Montgomery, 1866

Engraving, 6 7/8 X 8 15/16 in.

Fraunces Tavern Museum, TR2019.01.003. Gift of Kent D. and Tina K. Worley.

This engraving reproduces Alonzo Chappel's oil painting, The Death of General Montgomery. It depicts General Richard Montgomery's failed attack on Quebec City, which resulted in the Continental Army's retreat from the area. As his soldiers emerge from a hole sawed through the city's outer wall, they find themselves mired in an attack by a group of defenders, largely unseen out of the picture. Amid the resulting clamor, General Montgomery crumples in the arms of his comrades, bleeding from shots to his forehead and chest.

Engravings like this were often reproduced after an artist's oil paintings and commonly found in books. Typically, we see credits to both the engraver and artist, but you'll notice that this one lists only Chappel as the painter. At the height of his career, Chappel was so busy that he employed a group of artists to transform his oil paintings into engravings destined for print. Gregory M. Pfitzer remarks on the proto-Warholian nature of this process: "'Chappel’s factory' ... was so prolific and yet inconsistent in its work that the phrase 'based on an original oil painting by Alonzo Chappel' adorning so many of his illustrations in historical works and popular prints became synonymous with mechanized or processed art." [i]

UNKNOWN ENGRAVER, AFTER ALONZO CHAPPEL

(AMERICAN, 1828-1887)

G. WASHINGTON

LINE ENGRAVING, 10 1/2 X 7 7/8 IN.

FRAUNCES TAVERN MUSEUM, TR2019.01.012. GIFT OF KENT D. AND TINA K. WORLEY.

The nineteenth century saw massive developments at all levels of American society and culture. Urbanization, immigration, and new technologies of the Industrial Revolution fueled commodity production to soaring heights. An influx of immigrants drawn to the promise of a prosperous life saw the United States population quadruple between 1814 and 1860. By the end of this period, the U.S. was a major manufacturer whose production levels were exceeded globally only by England and France. This included a burgeoning print industry that served a growing literate population. By the mid-century, 90 percent of white adult U.S. residents could read, and new printing presses were able to affordably produce books for the masses. [ii] 19th century Americans therefore most often encountered images from the history painting genre not in the gallery, but on the pages of their books. [iii]

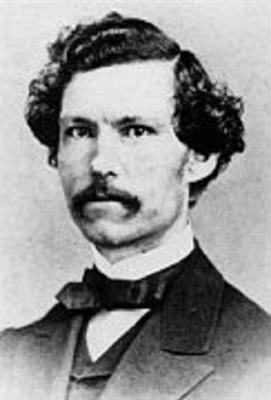

Proliferator of these scenes, Alonzo Chappel was born in 1828 in New York City. His parents came from modest means but supported his desire to become an artist from an early age, and Chappel notably began his career offering portraits to passersby on the streets of Manhattan for five to ten dollars apiece as a child. [iv]

Rather than rely on the preference and taste of an entourage of wealthy patrons, Chappel earned his income through commissions from Henry Johnson, owner of leading illustrated book publisher, Johnson, Fry and Company. Working directly with publishers gave artists the ability to bring their work to audiences of unprecedented scale. Johnson worked closely with Chappel on his two best-known passion projects: A Visual History of the United States and National Portrait Gallery of Eminent Americans.

Despite his success in illustration, Chappel desired to be seen as an academy artist and continued to exhibit his oil paintings in shows at the National Academy of Design and the Brooklyn Art Association. [v] Even though artists like Chappel worked across mediums, their involvement in illustration continued to be seen as a lesser vocation in the eyes of the cultural elite. Richard McLanathan notes, dipping one's pen into the ink jar of the printed medium "deprived [one] of the elevated status of artist." [vi]

At a time in art we now associate with the rise of European Impressionism and the avant-garde, Chappel looked back to the Revolutionary Era and the formation of the country as his subject matter. In publications like Johnson's History of the United States and prints such as Death of General Montgomery, Chappel played an active role in visualizing the figures and events of the country's recent past, a time before artists and photographers bore firsthand witness to battle (the National Gallery of Art went so far as to refer to the Revolutionary Era as a "sparsely documented epoch" in the 1944 catalog for its exhibition, American Battle Painting, 1776-1918). [vii]

The confluence of new printing press technology and a large, literate audience in the new nation suggests that Chappel had the ability to take advantage of this new intellectual climate he found himself in. Few of Chappel's oil paintings survive in the public eye today, but the illustrations produced by his ‘factory’ continue to be commonly found in books and prints like this one. Much like his refusal to choose between the role of fine artist or professional illustrator, Chappel's art serves as both art and historical record, whether or not it was accurate; Montgomery died of shots to his head, groin, and thigh, not his chest. [viii]

Nevertheless, Chappel’s work, along with that of his companions in the history genre—Jonathan Trumbull, Emmanuel Leutze, and John Ward Dunsmore—dictated how we remember the history of the Revolution and early republic.

Citations

[i]: Gregory M. Pfitzer, “Portrait of Alonzo Chappel as Artist,” Clio Visualizing History, 2002, cliohistory.org/visualizingamerica/picturingpast/part-two/singular-agendas/artistchappel.

[ii]: David Jaffee, “Industrialization and Conflict in America: 1840-1875,” The Met Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, April 2007, metmuseum.org/toah/hd/indu/hd_indu.htm.

[iii]: Barbara J. Mitnick, “Paintings for the People: American Popular History Painting, 1875-1930,” in Picturing History: American Painting 1770-1930, ed. William Ayres (New York: Rizzoli, 1993), 164.

[iv]: Pfitzer, “Alonzo Chappel.”

[v]: Mitnick, “Paintings for the People,” 164.

[vi]: Richard McLanathan, foreword, The Brandywine Heritage (Greenwich, Conn.: The New York Graphic Society, 1971) 71.

[vii]: National Gallery of Art (U.S.), American Battle Painting, 1776-1918 (Washington, D.C. and New York: Smithsonian National Gallery of Art and Museum of Modern Art, 1944), 5.

[viii]: Hal Shelton, General Richard Montgomery and the American Revolution, (New York: New York University Press, 1994), 149.

Bibliography

Jaffee, David. “Industrialization and Conflict in America: 1840-1875.” The Met Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History, April 2007. metmuseum.org/toah/hd/indu/hd_indu.htm.

McLanathan, Richard. The Brandywine Heritage. Greenwich, Conn.: The New York Graphic Society, 1971.

Mitnick, Barbara J. “Paintings for the People: American Popular History Painting, 1875-1930.”

National Gallery of Art (U.S.). American Battle Painting, 1776-1918. Washington D.C. and New York: Smithsonian National Gallery of Art and Museum of Modern Art, 1944. moma.org/calendar/exhibitions/2319.

Pfitzer, Gregory M. “Portrait of Alonzo Chappel as Artist.” Clio Visualizing History, 2002. cliohistory.org/visualizingamerica/picturingpast/part-two/singular-agendas/artistchappel.

Shelton, Hal. General Richard Montgomery and the American Revolution. New York: New York University Press, 1994.