Object of the Month: Lafayette and His Military Legacy at Fraunces Tavern Museum

By Jack Campbell

Programs & Events Associate Jack Campbell explores the life of the Marquis de Lafayette and his legacy at Fraunces Tavern Museum.

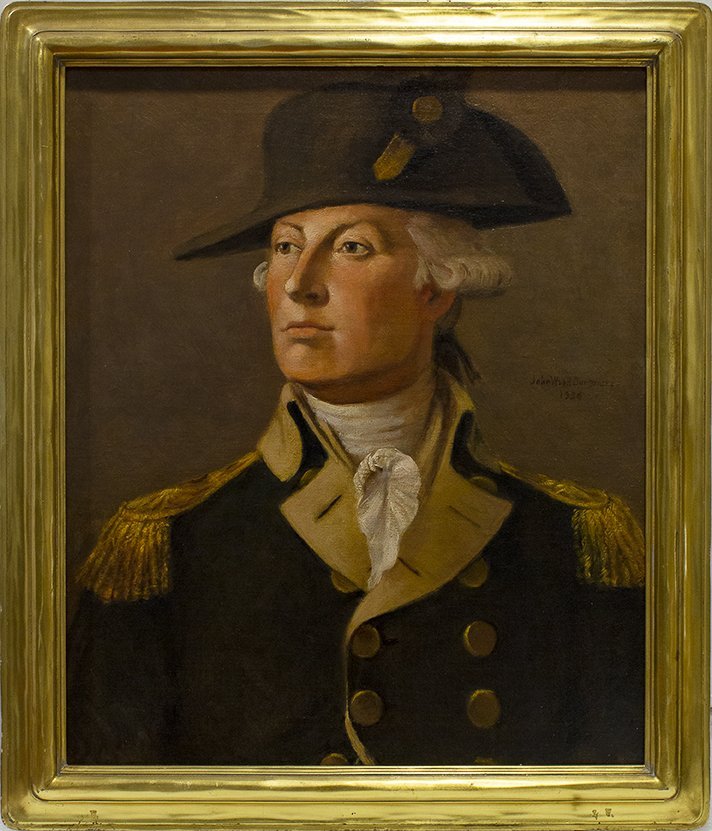

Nicknamed the "Hero of Two Worlds," the Marquis de Lafayette is one of the most revered figures in American history. Born Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette, and known simply as "Lafayette" in America, he was a French nobleman, musketeer, and officer. At the age of 19, the young man arrived in the rebelling colonies hoping to find glory on the battlefield. He was one of many ambitious foreign officers to offer their services to the Americans, causing large numbers to have their services turned down. However, Lafayette impressed General George Washington with his abilities, personality, and willingness to forgo a salary and pay his way. The two developed a bond that was so close that it is often described as a father-son relationship. Lafayette's father died during the Battle of Minden in 1759, and Washington had no biological children of his own, though he did raise Martha's as his own. Washington may have acted as the father Lafayette always wanted, and Lafayette as the son Washington had always wanted. Lafayette would even name his only son after Washington. [1]

The Battle of Brandywine

Among the battles that Lafayette fought during the Revolutionary War was the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. During the battle, a musket ball struck his thigh. It is believed he wrapped his leg with the red sash he was wearing at the time. The injury would keep him out of action for months. The sash was an essential part of high-ranking officers' uniforms as it distinguished their rank. It was a practice that was common in the 18th and 19th centuries. Officers throughout the army likely would have worn them. The sash would become stained with Lafayette's blood which is still visible today.

Lafayette would present the sash and other possessions to American Colonel Heman Swift when he returned on his grand tour of the United States decades later. They were described as "old army friends," and the sash would pass down through the Swift family for generations. In 1915, Dr. Edwin E. Swift, a member of the Sons of the Revolution in the State of New York, donated it to Fraunces Tavern Museum. Dr. Swift was a direct descendant of General Swift.

Lafayette's Legacy

Lafayette would serve throughout the American Revolution, becoming one of its greatest heroes. He would travel to France to help gain support for the cause and lead American forces into battle until the very end of the war. The fighting Frenchman would remain a beloved figure in the country he helped create for the rest of his life, and that devotion remains today. In addition, he would remain active in global politics for the rest of his life, especially in France.

His role in the French Revolution would see him and his family imprisoned for five years in Austria. [2] His son Georges Washington Lafayette fled to America. There, navigating the difficult politics of the situation, he would stay under the care of his father's friend President George Washington. [3]. Lafayette would continue to remain active in French politics upon his release, becoming one of the country's largest-looming figures. A staunch abolitionist, Lafayette was outspoken with his anti-slavery views and tried to convince Washington to free the enslaved population at Mount Vernon. [4]

In 1824, he embarked on a grand tour of the United States that included stops at every state and visits to his former friends such as retired Presidents John Adams and Thomas Jefferson. He would visit Washington's Tomb and take soil from Bunker Hill. When he died in 1834, the soil was poured over his casket so that his final request would be granted: to be buried in both French and American soil.[5]. An American flag is always found flying over his grave in Picpus Cemetery in Paris.[6]

Lafayette at Fraunces Tavern Museum

The memory of Lafayette has been honored at Fraunces Tavern Museum through the preservation and display of artifacts related to him. In 2015, the museum debuted Lafayette, which featured pieces related to his visit to the United States, including calling cards and a pair of officer's pistols. Many others commemorated him, whether at his return to America or his death. A memorial badge worn by a mourner at a parade honoring him was among those related to his death. These artifacts allow the museum to display Lafayette's memory to the public and further the history of the Revolution.

Bibliography

Johnson, Kate. "Georges Washington de Lafayette." George Washington's Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/georges-washington-de-lafayette/ (accessed January 19, 2022).

Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union. "Washington's Changing Views on Slavery." George Washington's Mount Vernon. https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/slavery/washingtons-changing-views-on-slavery/ (accessed January 19, 2022).

Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau. “Cimetière de Picpus.” Cimetière de Picpus. https://en.parisinfo.com/paris-museum-monument/71410/Cimetiere-de-Picpus (accessed February 4, 2022).

Unger, Harlow Giles. Lafayette. (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002).

Footnotes

[1]Harlow Giles Unger, Lafayette, (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2002), 107.

[2]Unger, Lafayette, 316.

[3]Kate Johnson, "Georges Washington de Lafayette," George Washington's Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/library/digitalhistory/digital-encyclopedia/article/georges-washington-de-lafayette/ (accessed January 19, 2022).

[4]Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union, "Washington's Changing Views on Slavery," George Washington's Mount Vernon, https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/slavery/washingtons-changing-views-on-slavery/ (accessed January 19, 2022).

[5]Unger, Lafayette, 380.

[6]Paris Convention and Visitors Bureau, “Cimetière de Picpus,” Cimetière de Picpus, https://en.parisinfo.com/paris-museum-monument/71410/Cimetiere-de-Picpus (accessed February 4, 2022).